Nino puts on her a jacket, takes her umbrella, and walks out.

Her first stop is at the front gates of her house. This is where the mobile internet reception should work best. The call comes but as soon as she greets her teacher the connection cuts out.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reconnect, Nino walks into her neighbor's garden further up the hillside, to find a more elevated position.

Finally Nino gets the signal in the middle of the garden plot, but it's too cold to stand there.

The thermometer outside the house reads 2 degrees Celsius. She tries moving about to warm herself up, but after taking a few steps the internet connection is cut off again.

"I can not hear anything. I'll call a classmate or the teacher on the phone later to get the homework, but often I can't even complete my assignment. Because I need an internet connection for that, which we do not have," says Nino.

Nino has four younger siblings, but the family only has one smartphone. So they take lessons in turn.

7-year-old Lusi, the youngest in the family, is a second-grader. To attend her online lessons, she also has to stand outside.

Lusi's older brothers and sisters take special care trying to keep her from catching a cold.

In Kvemo Svaneti snow arrives early, sometimes in late October, and stays until April. It can reach up to a metre deep.

The village of Leusheri, where Nino's family lives, is 1040 meters above sea level. It lies in the shadow of Tekali mountain, over 3043 meters high.

Only 40 residents live in Leusheri, which is surrounded by mountains. In the 2002 census there were 110 people living there.

"There are just 7 students in our village in the school - four of us siblings - and three other children. We do not have good internet because probably no one cares about such a small school. It is very difficult for us to study without the internet.

There are no options to attend extracurricular activities in the village. We don't even have a library. The internet is the only way to fill this gap, but we do not have a decent connection. That's why some parents who can afford it take their children elsewhere. Young people see no prospects here and want to leave. The villages are getting emptied. The fact that you were born and raised here, and love this place, is not enough to remain here, we need to have better living conditions. We may not be able to turn Svaneti into a city, but why can't we have a reliable internet connection?" says Nino.

Nino reads 13 subjects, including history and cultural studies. Four of those subjects are taught by her teacher Indira Bendeliani.

"Here, in the mountains, the internet is either of poor quality or does not exist at all, it's not even worth talking about WiFi. During online lessons we often lose the internet connection. So, I have to call each child individually on my cell phone and explain the subject. Children in highland villages do not have the same level of education as in the urban areas. Due to the pandemic, the Ministry of Education offered us to teach by making use of TV programing, where students are given various video lessons, but in the mountains of Georgia, the digital connection is so poor that children cannot benefit from this resource," says Indira Bendeliani.

In the public school of the village of Choluri, Lentekhi municipality, there are 39 students and 19 teachers.

Teachers say that online lessons are not as effective, and students have to be taught the same thing again and again until they understand.

The Ministry of Education has yet to publish a study on the pandemic's impact on the quality of education.

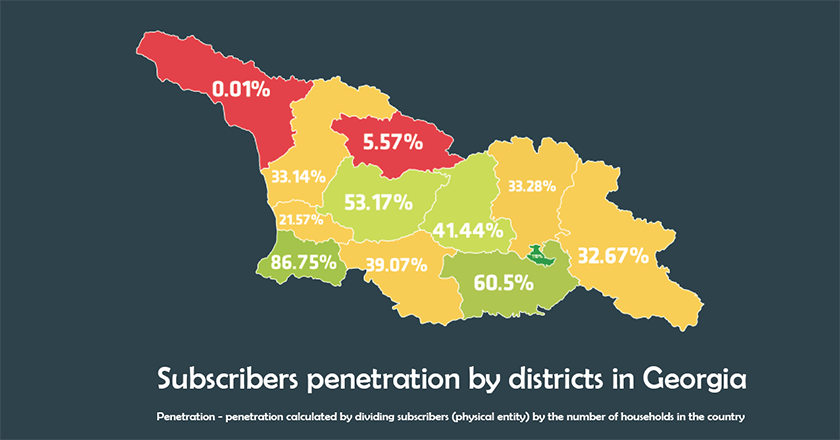

Racha-Lechkhumi and Svaneti are among the most remote Georgia's mountainous regions, with more than 400 villages, 4420 children are enrolled at 93 schools.

289 villages have no broadband internet, and mobile internet is only available in about 60 villages. With only low-speed mobile connections, children living in more than 250 villages have been left with no access to education during the pandemic.

The cost of mobile internet in rural areas is higher than in the district centres. But according to the 2017 Constitution of Georgia "Everyone has the right to access the Internet and use the Internet freely" (Article 17).

Back in 2014, the country's governing Georgian Dream party, promised to deliver full internet access to the entire population of Georgia.

The following year, as part of its universal access policy, the Georgian Dream party pledged to introduce high-speed and cheap internet to 2,000 Georgian villages.

In February 2016, the Minister of Economy and Sustainable Development Dimitry Kumsishvili announced that the leader of the Georgian Dream Party, billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, would pay around $150 million USD to finance the cost of universal internet access in Georgia.

During the 2016 parliamentary elections, the Georgian Dream in its electoral campaign pledged the construction of 8,000 kilometers of broadband cabling to provide access to high-speed internet to 90% of the country's population.

But the program never materialised.

In its draft state budget for 2018, the government once again promised to return to its plans to carry out its program of providing universal internet access.

Ahead of the 2020 elections, Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia approved the strategy for the development of Georgia's broadband network for 2020–2025.

The project Log in Georgia is set to be completed by 2025.

The country's Minister of Economy Natia Turnava said that the World Bank would finance a $40 million universal internet initiative aimed at delivering high-speed internet to one thousand settlements across Georgia.

The program will only cover villages with populations of more than two hundred residents, and where private companies have no plans to provide internet access.

But in Georgia today, there are over 1500 villages, like Leusheri in Kvemo Svaneti, where Nino Khachvani lives, with a population of fewer than 200 people.

It turns out that 'internetisation', so proudly announced by the government, won't be "universal" after all.

And as long as the pandemic restrictions on schooling remain in place Nino and her siblings will continue to miss out on their education.

Author: Levan Oniani